|

World War One, the Erster Weltkrieg for the Germans, the names Douamont, Hindenburg Line, Arras, Bullecourt, Cagnicourt, Montfaucon in 1917 were known by millions of soldiers from Australia, Germany, France, Belgium, England and Canada. This article is about one German soldier who served there, was wounded and 50 years later went back to visit the old Western Front and some of the soldiers who are still there. Copyright 2024 by Richard O. Aichele and inforworks.com |

Return to the Western Front A German Artillery Soldier's Story by Richard O. Aichele Email Contact:- - richaichele@aol.com P.O. Box 4725, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 USA |

Fifty years was a long time but the names of towns and cities such as Noyon, Sompepy, Cagnicourt, Arras and Ciney were still familar. Eugen R. Aichele's memory in 1967 was still sharp and he found several places where the roads and terrain had not changed that much since 1917. The memories came back easily of handling the horses to pull the battery's field guns and the wagons to new positions while under artillery fire from the other side. Life on a farm had made him fairly expert at handling horses - then also still the prime mover of armies and artillery pieces in 1916. The construction of a industrial mill and electric hydro power plant in his hometown gave him some experience with modern machinery. After training, he was assigned as a Kanonier to the Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 serving on the Western Front. He then spent almost three years with that regiment amid the mud, shell fire, gas, attacks, retreats, rain, snow, life and death that made up daily life of soldiers on both sides of the front lines in France and Belgium. There were always recollections of those days long past. Alarm: Under heavy enemy bombardment, bringing the horses forward in the dark at 3 AM to the battery's position then fighting the mud to pull the guns to a new position further back to be ready for action before the expected enemy infantry attack in the morning. Foraging: Taking a team of horses and a wagon down a road under enemy artillery fire into a valley and into the remains of a town in temporary no-man's land to bring back some food for the battery and the horses. And, with a stroke of luck, finding an undamaged supply of the region's French red wine intact in barrels at a destroyed winery and bringing a small supply back to the gun battery's position. Under Heavy Artillery Fire: Seeing a pair of horses, a wagon and its two riders on a road not far ahead completely disappear due to a direct hit by a heavy shell. |

| Day after day, this soldier and every soldier lived hearing sounds of explosions among desolation and death in the trenches, no-mans land and behind the front lines along the Western Front. Small cities and towns destroyed with often a church ruins were the most recognizable landmark remaining. Photos above from Eugen R. Aichele's collection were taken in the Cagnicourt - Montfaucon - Arras region of the Front. |

Your interest in this period of the Great War is appreciated. Please email any comments to: richaichele@aol.com Thank you. Merci. Tack. Gracias. Vielen Dank. |

|

The First Battle of Arras For Germans, it was der Arrasschlacht.". For Australians, it was The Battle of Bullecourt. April 11, 1917

The Arras - Bullecourt attack ordered by British Major General W. Holmes began on April 11 at 4:30 AM. The primary attacking forces were the Australian 4th Division's 4th Brigade and 13th Brigade to be supported by British tanks and artillery. The attack had been scheduled for April 10 but the supporting British tanks did not arrive so the attack was postponed until April 11. It had been decided by the English commanding general that there would not be the normal pre-attack artillery bombardment of the German defenses because the tanks would be sufficient. The next day, April 11, according to www.anzacsinfrance.com: "By the start of the attack only 3 tanks had arrived to assist the Australians. Most supporting tanks failed to appear. When engaged these tanks proved unreliable and too slow so the Australians proceeded without them. The tanks failed to even reach the wire and by 7am they were all burning. With no tanks or artillery the Australians fought their way to occupy sections of the Hindenburg Line, with parts of the Australian 4th Division occupying the Hindenburg Line without artillery assistance. They sent up flares asking for artillery support fire on Reincourt, 1.5 kilometres from Bullecourt, a position from which they were receiving machine gun and rifle fire. However, the support failed to arrive and the Australian 4th Brigade found themselves cut off by enemy shells, machine guns and counter attacking infantry. Incorrect reports had suggested that the attacks were successful and therefore artillery support was unnecessary. They had no option but to withdraw." "On the left flank of the Australian front, closer to Bullecourt, the 12th Brigade of the Australian 4th Division was also intensely engaged. German troops on either side of the Australian 48th Battalion and a portion of the Australian 47th Battalion worked their way behind the Australians. This now meant the Australians were completely surrounded. Under Captain A.E. Leane, the men of the Australian 48th attacked and captured the trench to their rear. Now artillery from the 5th Army began to fall, but it fell on the Australians. Again, there was no option left but to withdraw." Major Zimmerle's account also reported that in the morning came the alert that the "enemy had broken though into our trenches. Our infantry then counterattacked supported by German artillery fire." According to www.anzacsinfrance.com: "The battle had lasted 10 hours, with shooting ceasing at about 2 pm. The 4th Brigade took 3,000 men into battle and sustained causalities of 2,339. The 12th Brigade took 2,000 into battle and lost 950. Part of these casualties included 28 officers and 1,142 men captured, by far the most prisoners taken in a single battle during the whole war. The reason for this was the fact that the attack by the Australian 4th Division had actually breached the Hindenburg line but been left isolated and unsupported by inadequate artillery fire."

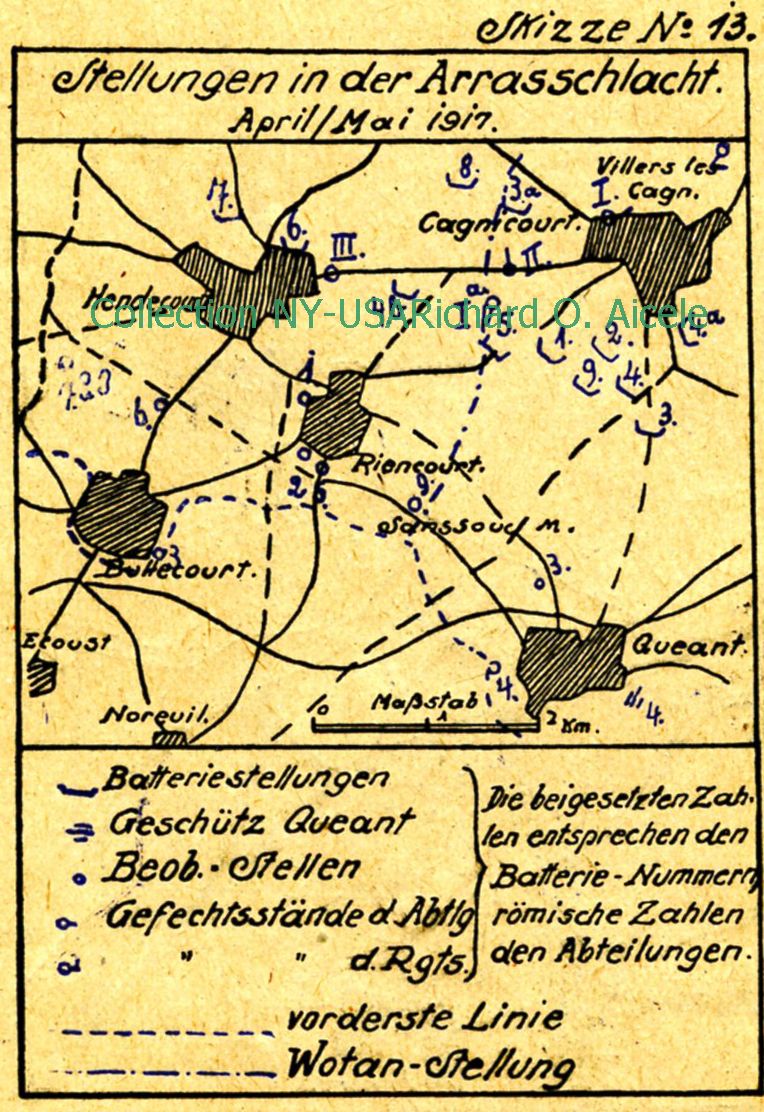

April 12, 1917 Major Zimmerle's regimental history of the Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 recorded there was a pause in artillery firing (called "feuerpause"in German Army records) that began after the battle actions of April 11 around Bullecourt and the withdrawal of the attacking Australian forces. The 49th FAR's gun positions shown on the map above outside of Cagnicourt were as close as 3 Kilometers from Bullecourt and 1 Kilometer from Riencourt.

Credit; Royal Flying Corps. Photo Source: McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Aerial photo above shows the town of Cagnicourt after the battle still behind the German front lines. Zig-zag line toward bottom and on left is a line of German trenches.

On April 12, 1917, the day after the battle, an entry in the English Royal Flying Corp.'s War Diary - Intelligence Summary reported that an airplane from a English squadron based at St. Andre, France had coordinated with a English artillery unit near Cagnicourt: "Artillery with aeroplane observation successfully engaged three hostile batteries." Credit; Royal Flying Corps. Source: Empire State Aerosciences Museum, Glenville, NY USA On April 12, the feuerpause ended suddenly. Major Zimmerle noted that "Earlier, low flying English airplanes had observed the gun positions of the 49th FAR's Batterie 4 outside of Cagnicourt."

The records of the Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 stated: "Heavy English shell fire scored direct hits on Batterie 4 that destroyed three guns and their positions. Wachtmeister Munding, Unteroffizier Manner, Kanonier Benhl and Sanitatsoldat (medic) Gerster were killed immediately. Unteroffizier Weis died later from his wounds. Kanonier Breisch was severely wounded and two other Kanioniers were also wounded." Aichele was one of those wounded with head injuries by shrapnel from the exploding artillery shells. Aichele was treated at a Field Hospital behind the German front line for several weeks. In later life, with a wry smile he would recall the first doctor saying, "I only lived because I had such a thick head." After several weeks in the Field Hospital, he was transported by Army Hospital Train to a larger hospital in Ludwigsburg, Germany where he arrived on May 9. Due to the severity of the wounds, on June 20 Eugen R. Aichele was sent by another Army Hospital Train to a Jena, Germany hospital specializing in treating head wounds. On August 15, he was discharged from that hospital, awarded a Iron Cross medal, given a short leave to visit his family, then went back to Western Front line active duty.

In May 1918, the Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 in which Eugen was serving was preparing for a new offensive at Noyon, France. Eugen did not know that his younger brother Ernst, then 18 years old, had been called up in November 1917. Four months later, after training, Ernst was sent to the same Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 as one of the replacement soldiers. One day, Ernst learned his brother Eugen's artillery battery might be nearby. During a brief quiet time, Ernst was able to find and surprise Eugen. The two brothers enjoyed a brief reunion on the Western Front.

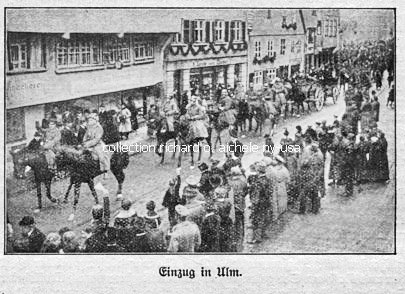

As the war neared its end, the 49th FAR suffered another 21 killed in September and 20 killed in October before the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Following the Armistice, the 49th began the long march back to their Kaserne in Ulm in southern Germany by way of Luxemburg, then through Germany along the Mosel Valley, crossed the Rhine River near Bingen and marched southeast reaching Ulm on December 22, 1918. He always recalled the challenging logistics of the German Army's planning that accomplished the organized withdrawal of millions of troops from the old Western Front eastward across the Rhine River as required by the Armistice agreement. A major factor was the German Army's divisions had to cross each others routes since some went home to northern Germany, others to southern Germany and others to the central part of the country.

The Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 after the armistice returned to its Kaserne in the city of Ulm. For the surviving soldiers, it meant going home. Years later, Eugen R. Aichele spoke of those events at the Arrasschlacht, being wounded, recovering and returning to the 49th Field Artillery Regiment for the remainder of the war on the Western Front. Later in life, when he talked about that experience there was a wry smile remembering a doctor at the front line hospital telling him, "That I only lived because I had such a Thick Head."

Remembering Those Who Served

During the 1920s and early 1930s, the Western Front visitors increasingly included those whose sons and husbands had made their ultimate sacrifices in bravery and endurance. Another visitor was Webb Miller, an American journalist who had reported some of the Western Front battles for the UPI. In his book I Found No Peace, published in 1936, Miller recalled that at the time of the battles "the cataclysmic horror of the war did not strike me with its overwhelming obscenity and futility until exactly eight years after it was over. On the eighth anniversary of the 1918 Armistice, I conceived the idea of visiting the old front to describe the appearance of the battlefields at that time. During the war I had been deluded, along with millions of others, by ignorance and propaganda into believing that the war really meant something..." "For two or three million living persons it meant something else," Miller observed but this time as a visitor to what had been the Western Front. Miller traveled though the battlefield areas using local trains. One trip in the Verdun area brought him together separately with two people seeking that "something else." Miller wrote in I Found No Peace, "In one corner of the shabby railroad compartment huddles a thin, careworn old German woman, poorly dressed in obviously homemade clothing. As the train drew up the slopes she nervously brushed the moisture from the rain-swept window for a last look at the desolate hills where more than 600,000 of her countrymen had been slaughtered. Then she subsided into the corner, weeping quietly, furtively dabbing her eyes with a sodden handkerchief. In broken French, she timidly asked me where she must change trains for Reims. I asked if she had lost relatives in the Battle of Verdun. She broke into tears. 'Yes, my two sons and my husband. Nobody knows where they fell. I could only walk over the terrible fields. I have been saving eight years to make this trip. I can never do it again. Everything is gone. Oh, this horrible war!' At the next station a stout French peasant woman in faded black entered the compartment. She took the other corner and stared silently through the window. At the junction I helped the German with her cane suitcase. She thanked me haltingly and stood uncertainly in the rain until the train left. Then I fell into conversation with the French woman. I told her about the German woman. The French woman kept silent for a few moments, then tears filled her eyes. 'The poor old woman,' she said. 'Our countries were enemies, but I can't help pitying that poor German woman. It must be terrible to come all this way and not know where her dead lie. I come every year at this time. My husband, my son and my brother are up on those hills. We know where their bodies lie; that is some consolation." |

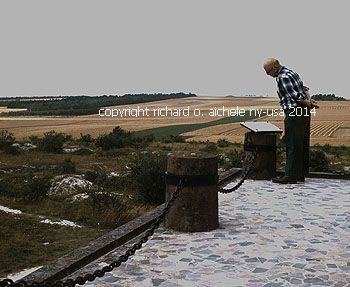

Those Who Remember Still Visit Eugen R. Aichele. a veteran of the Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49, was among the many Europeans that immigrated to the U.S. in the 1920s after the Great War to build a new life in a new country. But those experiences on the Western Front were never forgotten. Fifty years later, at the age of 70, Eugen R. Aichele was able to fulfill a personal mission to visit some of those places again. This time in peacetime. And then he was also able to share the experiences with his son Richard to carry on the mission of Remembering all the ordinary soldiers who served their countries.

A Visit To Old Friends

One of the first places to visit was the German Military Cemetary at Romagne, France. It was one of his many times of quiet rememberance and reflection for some soldiers he served with that did not come home after November, 1918 when the Armistice was signed.

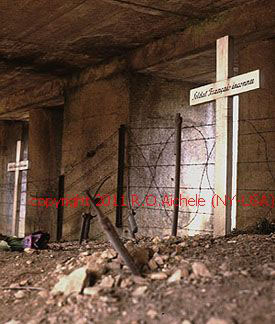

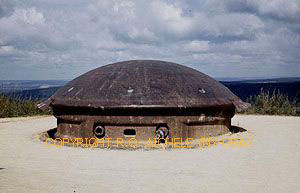

Fort Douamont Fifty Years ago before this veteran's visit, the Douamont fortress in Verdun, France was a place of strategic military and French national morale importance that millions heard about and fought to capture or defend. After heavy artilllery bombardments and repeated infantry attacks the main French fortress at Verdun was captured by German infantry and subsequently recaptured by the French after heavy fighting during the pivotal battles of 1916. This photo, taken after the battle when German troops had captured the fortress, shows the fort's entry from the moat as they found it.

In the years after the war's end in 1918, many German and French veterans finally had the opportunity to visit the remains of Verdun's forts and the battlefields that had been so important to the strategies of both armies. Photos show the main gun turret on the fort's top and the main tunnel deep inside the fort.

Visiting the remains of two smaller forts that surrounded Fort Douamont. (Above) An entrance to Fort St. Michel. (Below) Armament at top of Fort deTavannes.

The veteran studies a display map near one of the many monuments in the Verdun region and remembers a soldier's daily events of 1916 through 1918.

Remembering. Images of the Australian soldiers at the railway embankment during the April 1917 attack were captured by the British war photographer Captain Herbert F. Baldwin. The You Tube Video also shows the embankment site today, 100 years later, at peace.

The poignant Trench of Bayonets Memorial to the 170 unknown French soldiers who still stand there in their collapsed trench. For this German Army veteran, it was a place of the 1914 to 1918 war where Eugen R. Aichele again recalled the daily bravery and humanity of the ordinary French, English, Canadian, Australian soldiers, his fellow German soldiers, and in the war's last year, the American soldiers who fought on the Western Front.

In 1967, as Eugen R. Aichele, a Western Front veteran walked the different battlefields that were finally at peace, there was much reflection of what had gone fifty years earlier. He frequently just quietly commented: "And for what?" |

. . . . . . .

Listening to Veterans by Richard O. Aichele, Website Author There is a benefit of now being "older." In my case, it allowed me to be young enough to be able to listen to some Great War veterans of both sides. There were never stories of heroics. There were many memories of actions, of what they had to do and of those who were not there anymore after the shooting stopped. There were stories of compassion for enemy soldiers. There was an understanding that the ordeal had been shared by all at the front. -- - - - - - |

Other Information Works Great War Websites

|

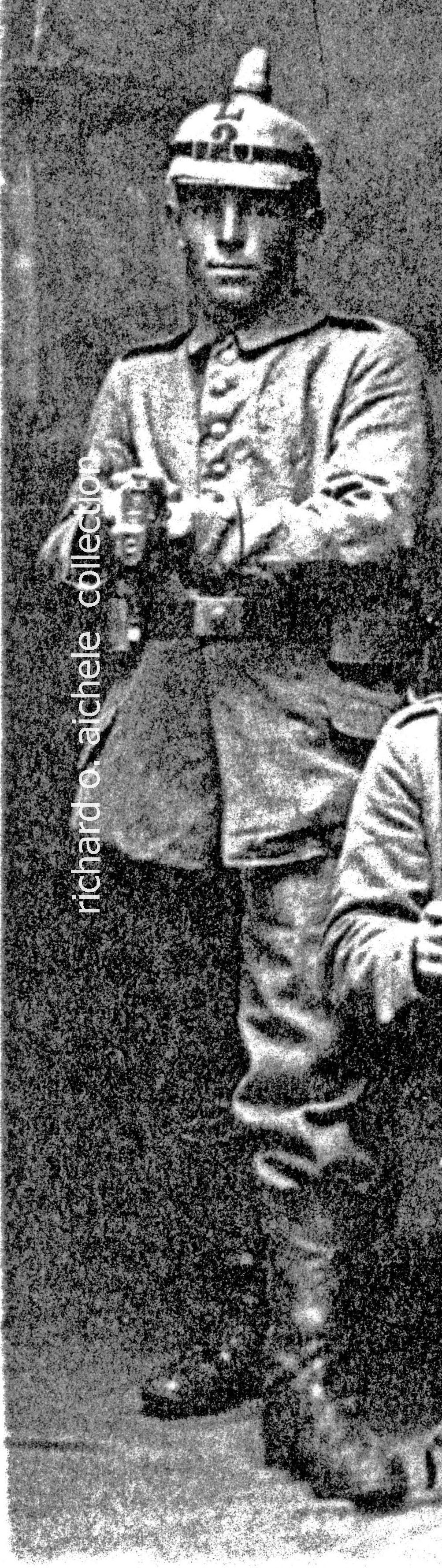

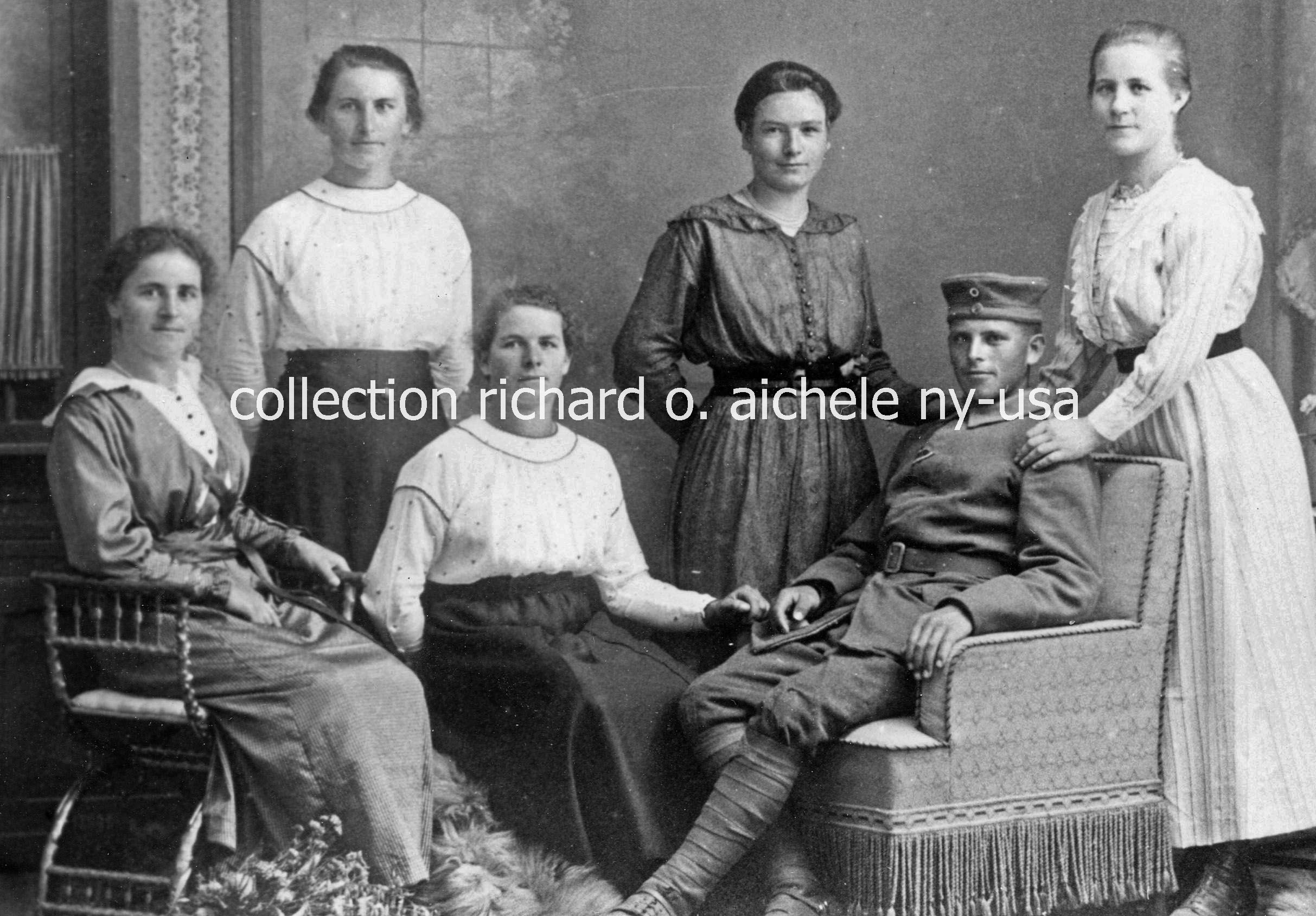

He came from a small farming town in Württemberg, Germany. The Great War was raging. On March 21, 1916 at the age of 18, Eugen R. Aichele was called up, entered the German Army and was trained in Ulm, Germany. Photo was at training graduation.

He came from a small farming town in Württemberg, Germany. The Great War was raging. On March 21, 1916 at the age of 18, Eugen R. Aichele was called up, entered the German Army and was trained in Ulm, Germany. Photo was at training graduation.

The German Siegfried (Hindenburg) line was strongly defended including protected gun positions and defensive pillboxes. In the Bullecourt area the defenses were manned by the Württembergische Infantry Regiment 120, Infantry Regiment 124 and Grenadier Regiment 123. The Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 field guns were in positions at Cagnicourt - Hendecourt according to Major Eduard Zimmerle with the 49th FAR.

The German Siegfried (Hindenburg) line was strongly defended including protected gun positions and defensive pillboxes. In the Bullecourt area the defenses were manned by the Württembergische Infantry Regiment 120, Infantry Regiment 124 and Grenadier Regiment 123. The Württembergische Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 field guns were in positions at Cagnicourt - Hendecourt according to Major Eduard Zimmerle with the 49th FAR.

Aerial photo showing smoke rising from Bullecourt.

Aerial photo showing smoke rising from Bullecourt.

On September 27, 1917 he arrived back on the Western Front rejoining the Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 then located near Ghent, Belgium. The unit was reorganzing after the Arras battles and preparing a new offensive in the Flanders area of Belgium. The 49th Feldartillerie Regiment moved back to the front lines on October 9, 1917. The later front line actions in 1917 included the long, heavy fighting at Ypres, Passchendaele, the Houthulst Forest sectors and the 1918 battles in France at Noyan, Matzbach and the Champagne region.

On September 27, 1917 he arrived back on the Western Front rejoining the Feldartillerie Regiment Nr. 49 then located near Ghent, Belgium. The unit was reorganzing after the Arras battles and preparing a new offensive in the Flanders area of Belgium. The 49th Feldartillerie Regiment moved back to the front lines on October 9, 1917. The later front line actions in 1917 included the long, heavy fighting at Ypres, Passchendaele, the Houthulst Forest sectors and the 1918 battles in France at Noyan, Matzbach and the Champagne region. During the heavy warfare of 1918 and until the end of fighting in November 1918, the brothers rarely saw each other since they were assigned to different gun batteries. Ernst served at times in the dangerous duty as a forward artillery observer for the artillery gun batteries located behind the rearmost line of trenches. Rows of barbed wire separated the trench lines. However, the observers for each battery were located in the forward `trench closet to the enemy trenches and were exposed to machine gun fire and hand grenades. The observers were connected to the battery by telephone lines laid on the ground. When enemy shellfire explosions destroyed the wires, the observers frequently were exposed while repairing the shot up telephone lines. In one such battle incident, Ernst had to pass through several lines of barbed wire, was wounded and lost the thumb of his left hand.

During the heavy warfare of 1918 and until the end of fighting in November 1918, the brothers rarely saw each other since they were assigned to different gun batteries. Ernst served at times in the dangerous duty as a forward artillery observer for the artillery gun batteries located behind the rearmost line of trenches. Rows of barbed wire separated the trench lines. However, the observers for each battery were located in the forward `trench closet to the enemy trenches and were exposed to machine gun fire and hand grenades. The observers were connected to the battery by telephone lines laid on the ground. When enemy shellfire explosions destroyed the wires, the observers frequently were exposed while repairing the shot up telephone lines. In one such battle incident, Ernst had to pass through several lines of barbed wire, was wounded and lost the thumb of his left hand.

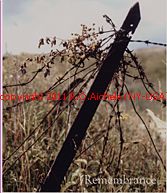

A wild flower bouquet dried by the summer sun on a barbed wire spike at the top of Verdun's Fort Douamont's moat that was left by a visitor in memory of those that made the ultimate sacrifice in 1916.

A wild flower bouquet dried by the summer sun on a barbed wire spike at the top of Verdun's Fort Douamont's moat that was left by a visitor in memory of those that made the ultimate sacrifice in 1916.

Remembering. Over the years since 1918, thousands of shell holes and miles of trenches were filled in by nature and by French residents who reclaimed the land for farms while rebuilding most towns and cities. Some small villages such as Fluery close to Fort Douamont were the scenes of such total destruction and thousands of deaths that they were left as memorials. They all help to also commemorate those many soldiers whose remains were never found and still lie there.

Remembering. Over the years since 1918, thousands of shell holes and miles of trenches were filled in by nature and by French residents who reclaimed the land for farms while rebuilding most towns and cities. Some small villages such as Fluery close to Fort Douamont were the scenes of such total destruction and thousands of deaths that they were left as memorials. They all help to also commemorate those many soldiers whose remains were never found and still lie there.