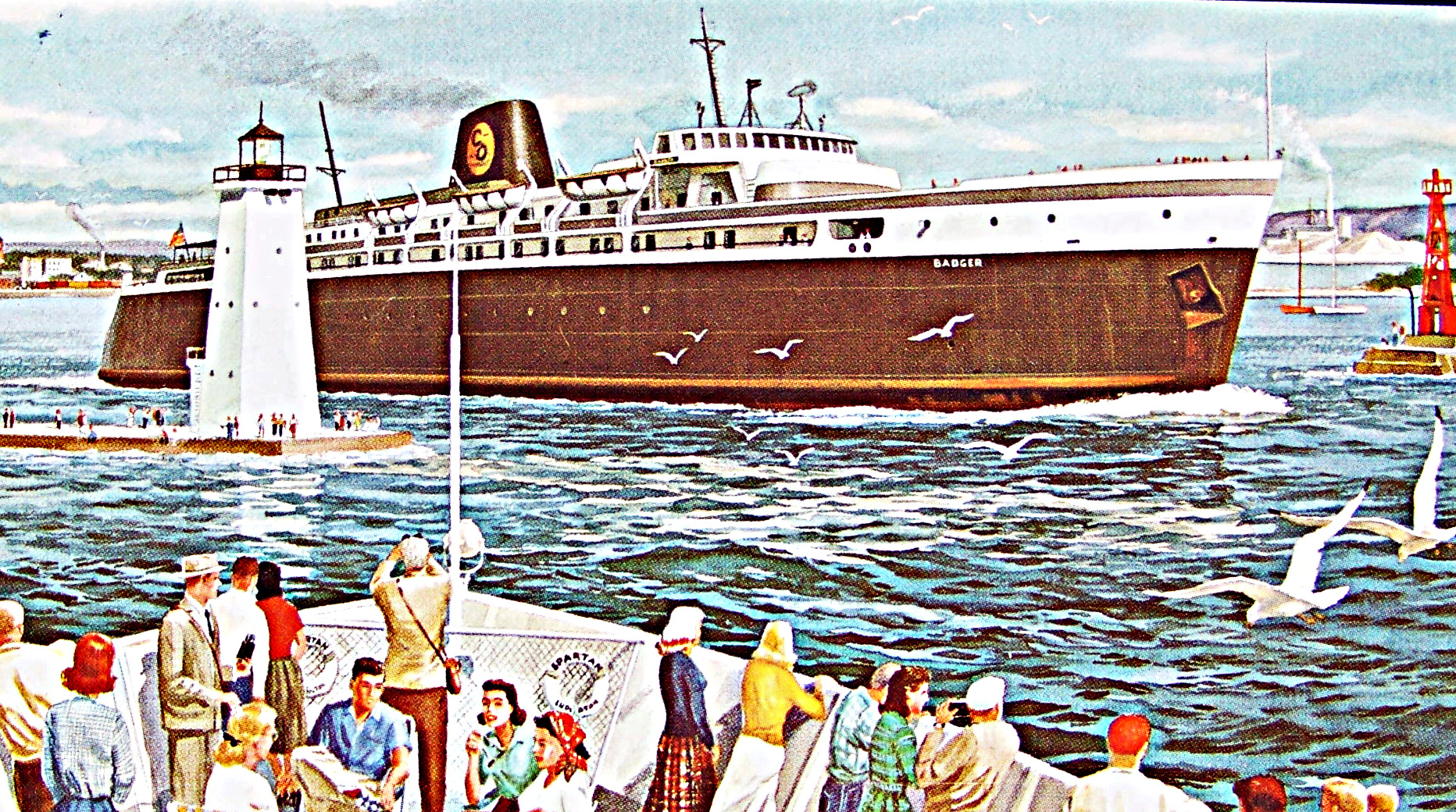

America's inland and coastal waters activity reflected 200 years of maritime history including riverboats such as the Delta Queen, harbor tugboats, ferries, the Great Lakes vessels including the S.S. Badger and the Edmund Fitzgerald.

|

America's Inland Waters |

Richard O. Aichele Email - - richaichele@aol.com

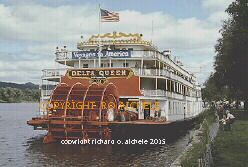

The steamboat Delta Queen sailed into the 1970s always greeting the river towns with happy songs from her Steam Calliope. |

The Delta Queen continued sailing into the 1980s on the inland waters of America's heartland calling at the river cities and smaller towns between New Orleans, Louisiana - St. Louis, Missouri -- St. Paul, Minnesota on the Mississippi River and up to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Cincinnati, Ohio the Delta Queen's home port on the Ohio River. For the passengers that enjoyed the leisurely crusing pace of the Delta Queen and the reassuring consistent sound of ther big paddle wheel at the stern, unforgetable memories were created. |

|

Working Harbor Vessels America's harbors and rivers were once crowded with tugboats, ferries and barges to transport people and cargo from one side to the other side. Many of the vessels were built and operated by the railroads where it was not possible for them to build bridges over the waters or tunnel under them.

The growth of container cargo ships in the 1970s and 1980s totally changed operations in New York Harbor and harbors worldwide. No longer were the individual finger piers that could only dock one or two cargo ships at a time where the cargo was loaded and off-loaded by cranes practical or efficient. The photo shows one of the Moran Towing tugboats assisting the soon to be retired U.S. Lines American Farmer cargo ship as it sailed from one of the old Hudson River finger piers in Manhattan, New York City.

Railroad Ferrries The ferry operations were a valuable part of the railroads' infrastructure. At one time, New York Harbor ferry operatrions were done seven days a week by six railroads each with their own ferry fleets linking their passenger trains with their passengers final destinations and two New York City municipal ferry operations linking Staten Island with Manhattan and Brooklyn. The New York - New Jersey Hudson River and lower New York bay municipal and railroad ferries carried hundreds or thousands of commuters daily on their ferries. The Erie Railroad's passenger and vehicle ferry Youngstown shown sailing up the Hudson River from the Barclay Street ferry terminal in Manhattan to its Jersey City ferry terminal on the New Jersey side.

The ferry Elizabeth was one vessel of the Central Railroad of New Jersey's fleet of ferries carrying passengers and vehicles across the Hudson River between New York City and the railroad's massive Communipaw Terminal in Jersey City, NJ. The ferries from Manhattan dockimg at the terminal offered direct connection passenger train service locally in New Jersey, to destinations such as Baltimore, Maryland; Washington D.C. and throughout Pennsylvania.

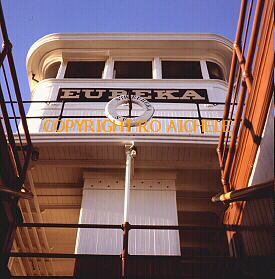

The New York area railroad ferries and tug boats are now gone and with with a few exceptions, the railroads' river front terminals are just fading history. However, in their prime, the crews of the railroad tugboats and ferries were a vital part of the railroads' overall daily operations. On the West Coast, the railroad operated ferry services were built to carry hundreds or thousands of commuters daily. One example were the ferries operated by the Southern Pacific Railroad in San Fransicco Bay. The

Eureka was once the largest double ended ferry in service sailing much of its life between San Francisco and Sausalito, California under railroad operation. The 299 ft. long boat with a 78 ft. beam could carry 2,300 passengers and 120 cars per trip. Built with a wooden hull, she was powered by a walking beam steam engine. Today the Eureka survives and rests at San Francisco's Maritime Museum. Aboard the Eureka the banks of benches inside provided comfortable seating on those days of foggy mornings when being outside might have been too cool. The waters of San Francisco Bay were home to many large ferry boats carrying passengers and vehicles for most of the 20th Century from 1928 to 1957. For commuters and travellers to towns around the bay, the pilot house on the Eureka was a familiar sight as they glanced upward while boarding the boat. |

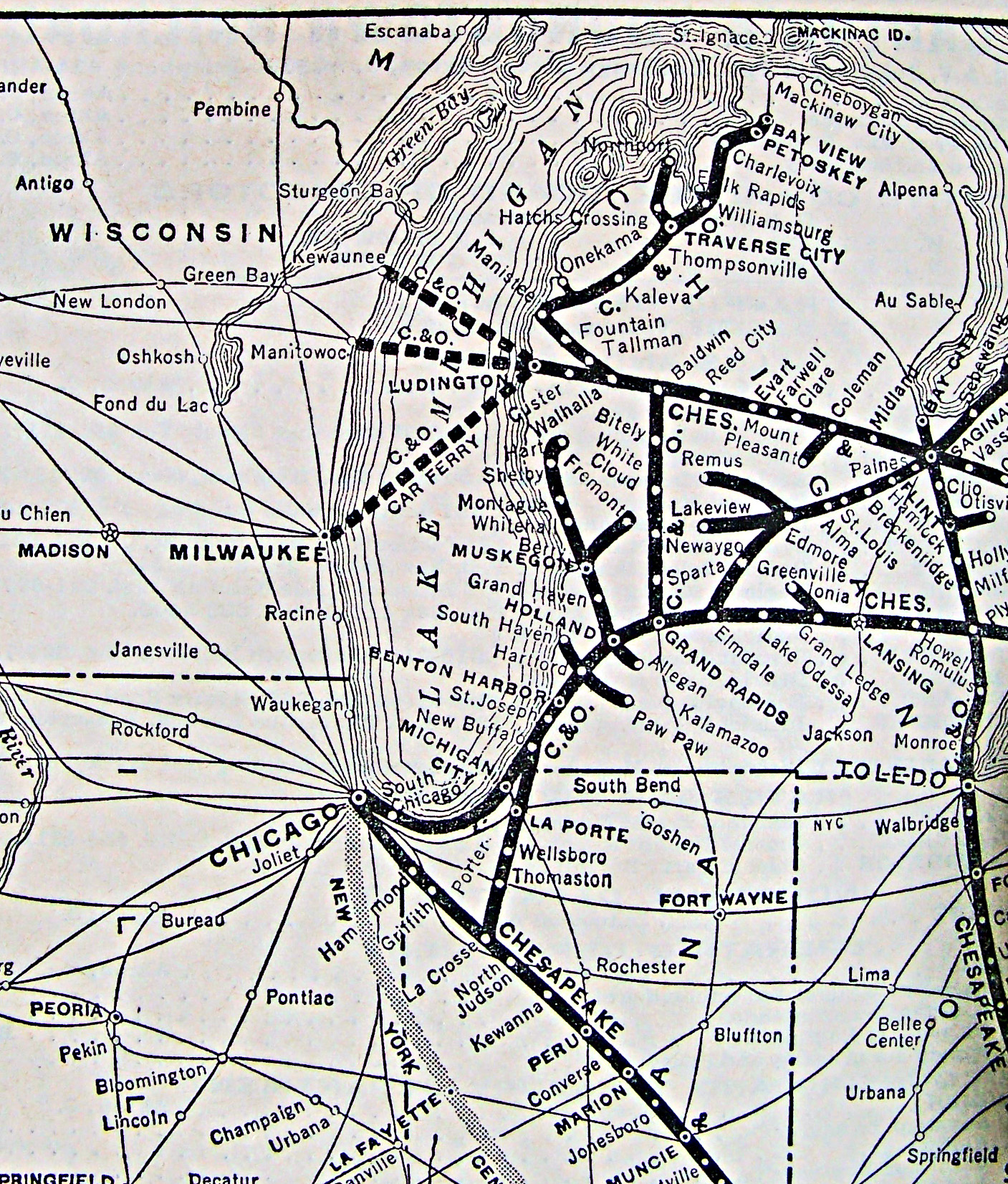

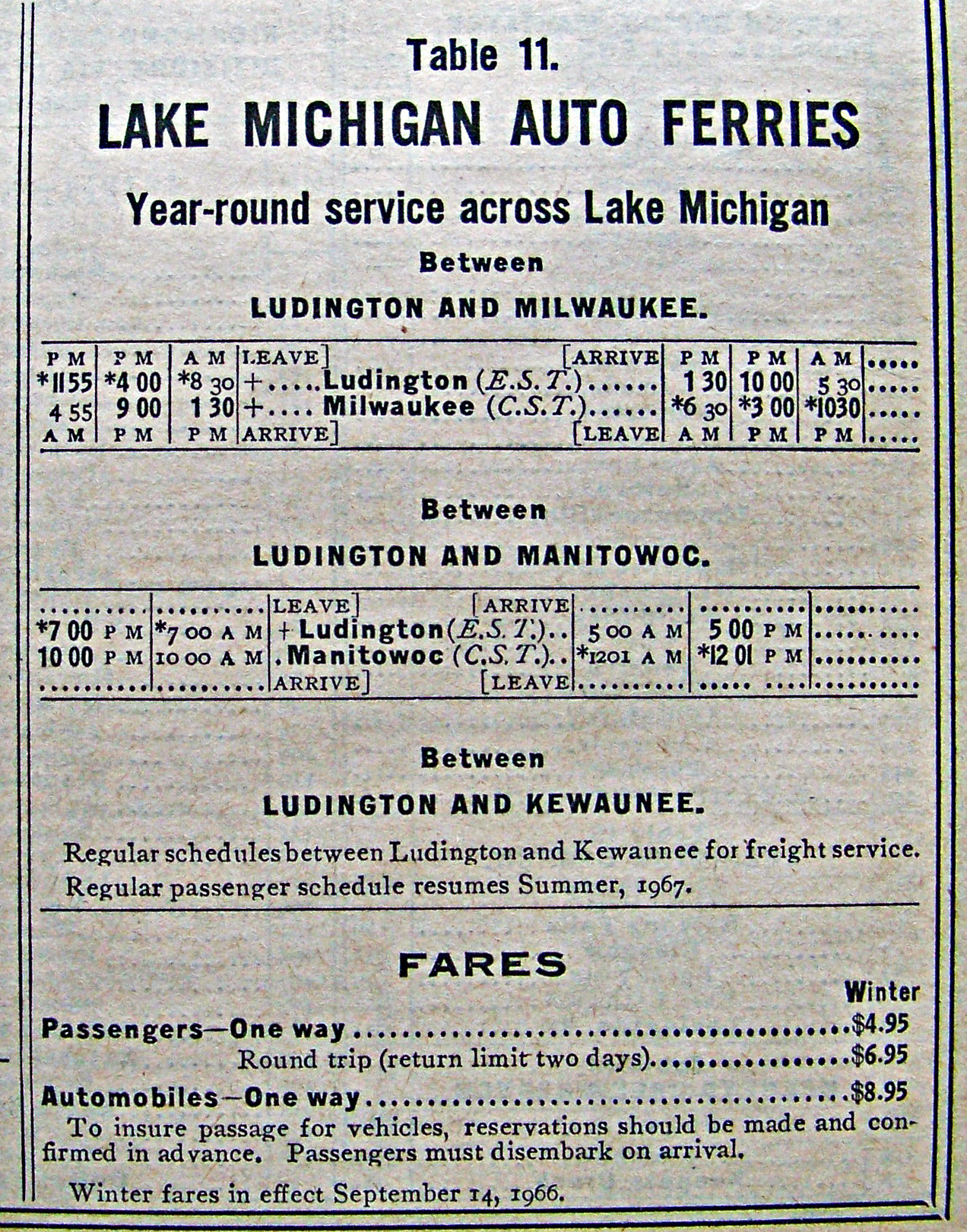

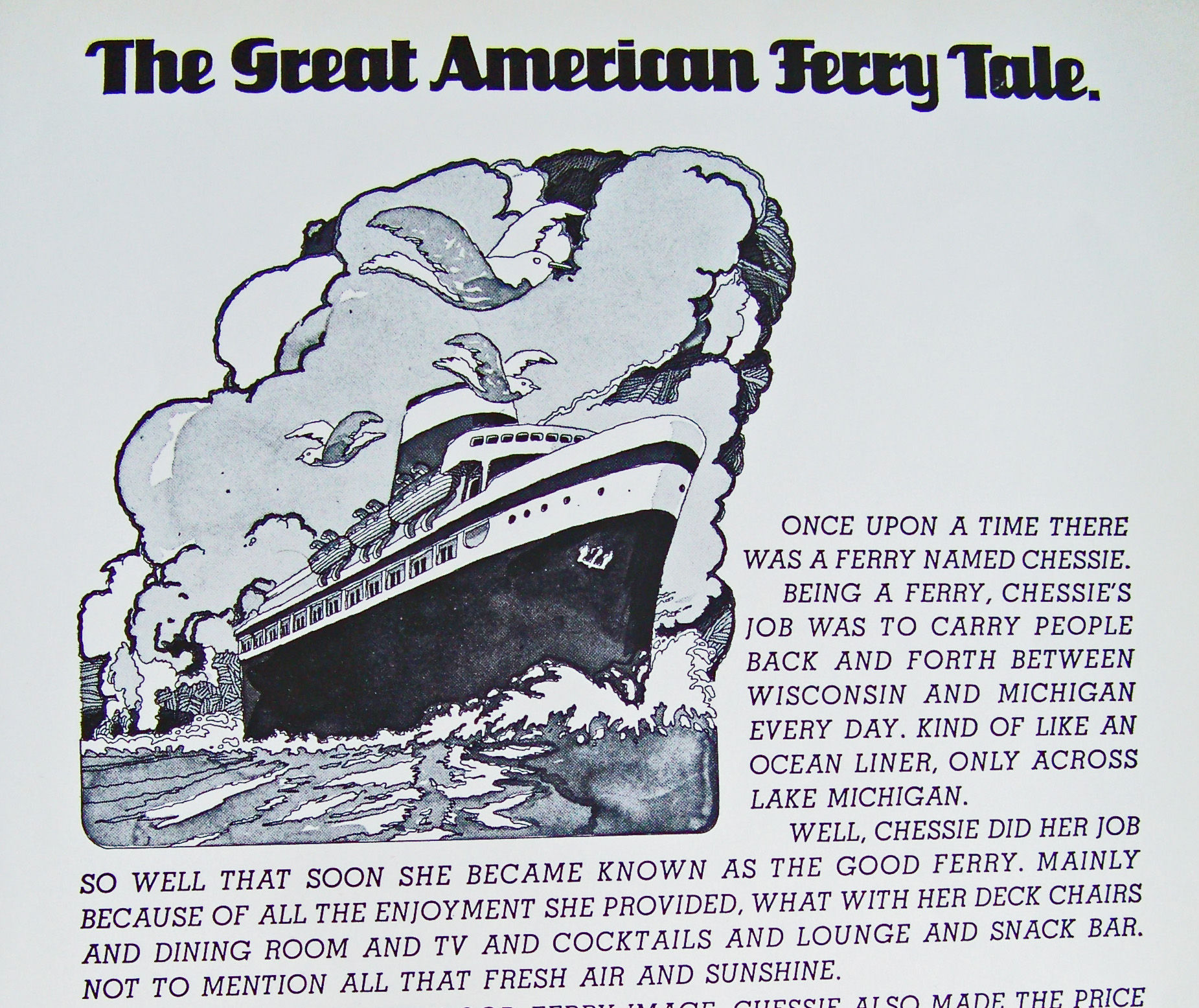

Lake Michigan's S.S. Badger The 410-foot S.S. Badger was built and launched in 1952 and entered daily service on March 21, 1953. The ship is the last remaining vessel in what was a fleet of seven ships capable of crossing Lake Michigan 365 days of the year transporting railroad cars, automobiles and passengers. The Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Railway Company began the ferry service early in the 1900s. It was their water links between the C&O's railroad lines at Ludington, Michigan and the railroad lines in Wisconsin going west from of the ports of Milwaukee, Manitowac and Kewaunee. According to a C&O advertising document in the 1950s, the ferry system carried: 175,000 passengers , 50,000 autos, and 100,000 railroad cars of freight annually across Lake Michigan. Vacationists from many states chose C&O's cross lake short cut as pleasant and restful interludes in a busy schedule. C&O's fleet of seven ships operate round the clock every day throughout the year. The C&O railroad ended the ferry operations in 1990. The S.S. Badger was saved by the Lake Michigan Carferry Service, Inc. based in Ludington, Michigan. The market still existed from private and commercial users because it avoided the extra miles and hours that would have resulted by passing through Chicago at the southern end of Lake Michigan. The new owners suspended the year round sailings during Lake Michigan's heavy winter ice season. Now during its operating season, the S.S. Badger makes approximately 450 of the 60 mile trips trips a year transporting passengers, autos, RVs, tour buses, motorcycles, bicycles, and commercial trucks across Lake Michigan between Ludington and Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The future of the S.S. Badger was in doubt several years ago because it was built to burn coal for the steam propulsion system. Environmental concerns focused on air emmissions but more seriously on the disposal of the coal ash, which has a mercury content, that was being discharged into Lake Michigan. Solving the problem were both legal and engineering challenges for the ship's owner. Several studies to eliminate the ash discharge considered many options including converting the ship to diesel engines or using LNG as a fuel. None were practical. However, EPA documents indicate that on August 16, 2012: Lake Michigan Carferry sent a letter to EPA Regional Administrator Susan Hedman stating that they learned of a new and more encompassing approach to ash retention that may make that option for controlling the ash discharge more viable than previously thought. The system is known as a Tubular Drag Conveyor and it automatically moves ash from the boilers to ash retention containers in the boiler room and then to ash retention containers located above on the car deck. One challenge was that type of system of ash retention had never been installed aboard a ship of that size before. Only thirty-three months later, the technical details of adapting the new ash handling system and perfoming the complex engineering and installtion work had been completed. The ash is now off-loaded and recycled as a material component used for road construction. Ash control was the major upgrading project goal but while that planning was underway Lake Michigan Carferry Service, Inc. also installed a new boiler combustion control installation to achieve cleaner burning of the coal and reduce those emissions. The cost of the two programs exceeded two million dollars. In May 2015, the EPA issued the letter that: EPA inspector confirms that the S.S. Badger mechanism to discharge coal ash has been removed and replaced with a system to retain coal ash. The new system will transport ash from the four boilers to four retention bins on the car deck. EPA required LMC to eliminate the discharge of coal ash into Lake Michigan by the end of the 2014 sailing season.

The environmental goals had been achieved. The investment of time and money had successfully put the S.S. Badger on a course for many more years of sailing on Lake Michigan. And the ship was again what the original owner, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company, had envisioned her to represent: The Great American Ferry Tale. |

Riverboat Memories in the 20th Century

|

For more Evolutions of Steamboats history Click Here To View The Steamboats |

Lake Boats Sailng Lake George, New York

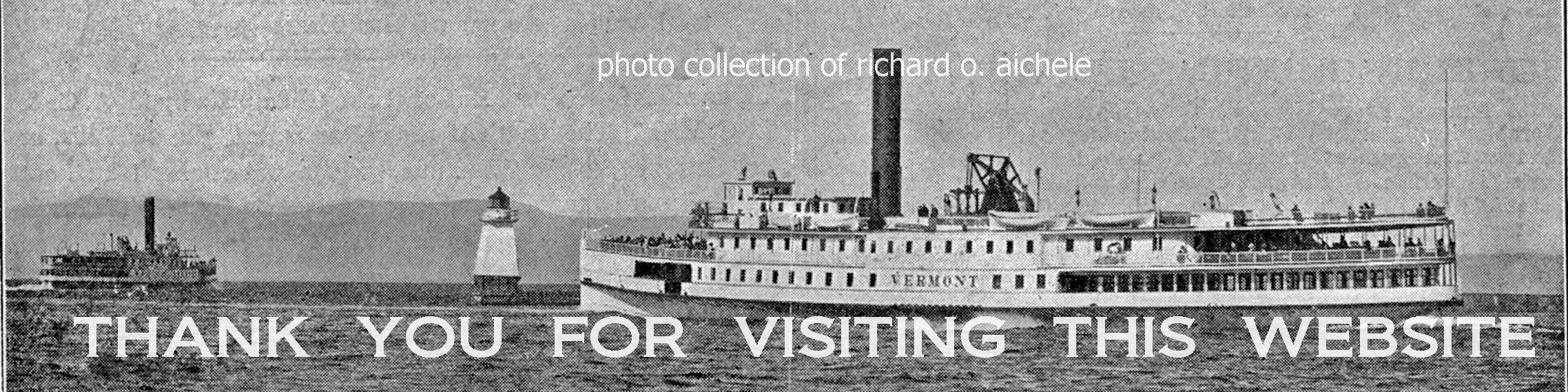

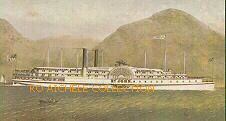

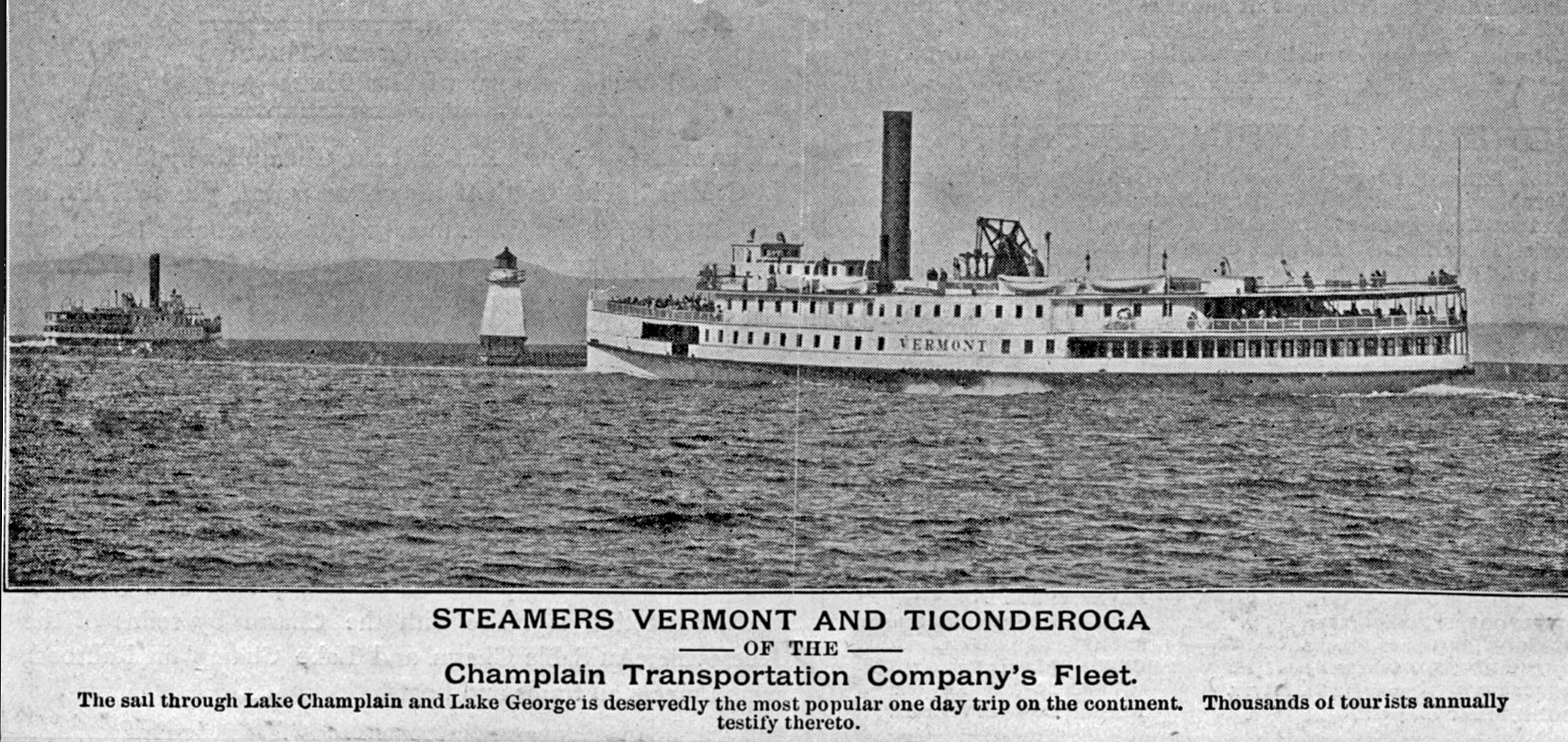

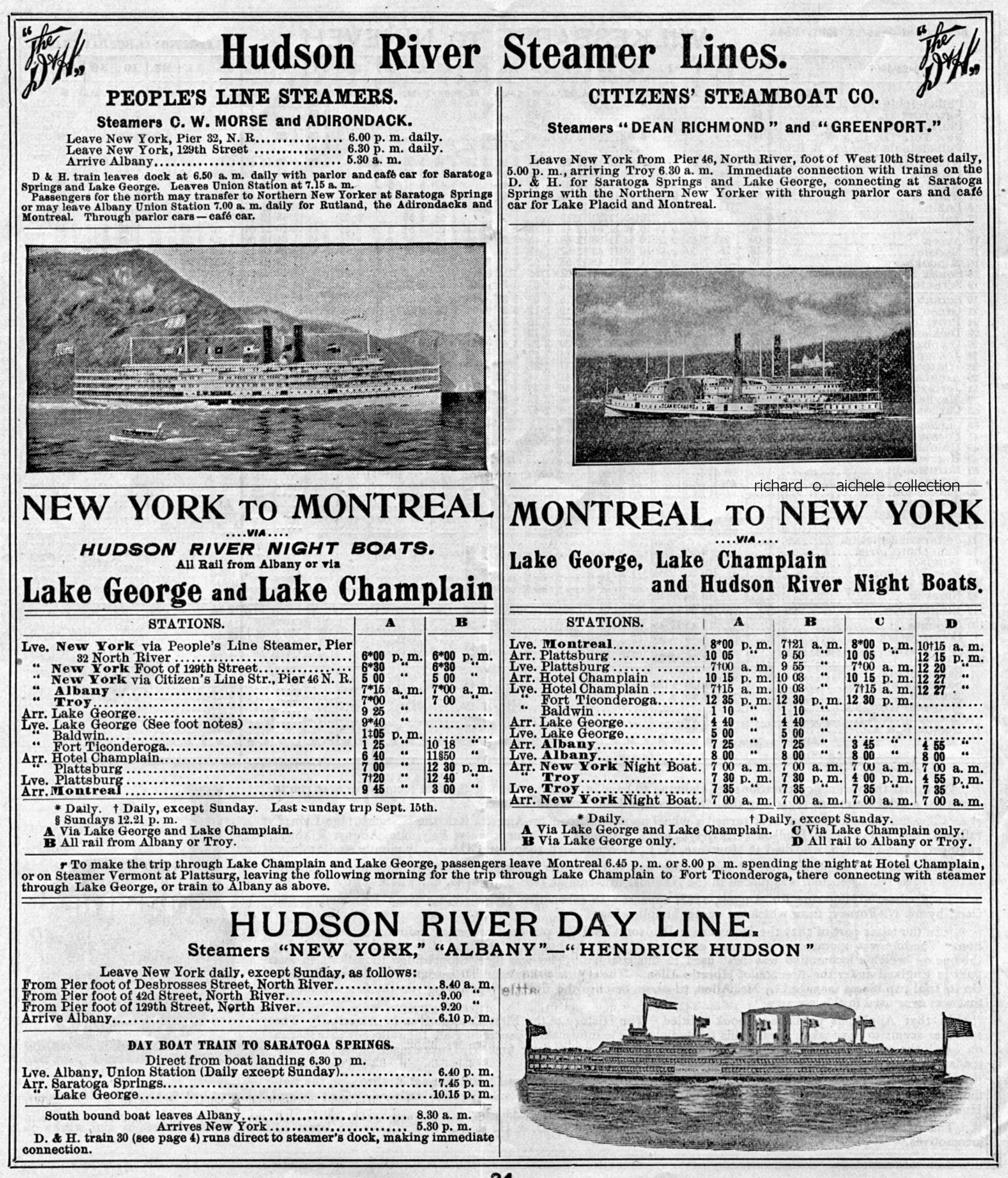

Steamboats appeared on Lake Champlain in Vermont and New York State in 1808 - only one year after Robert Fulton's Clermont first sailed under steam power. The next 63 years witnessed many new steamboats competing on that lake and nearby Lake George in New York State. In 1870, the two companies that survived the commercial competitions were bought by the Delaware & Hudson Railroad. That railroad, which operated trains between New York City and Montreal, Canada, realized the opportunity to expand passenger services for the growing number of people travelling from big cities to Vermont and the Adirondack Mountains in New York State. The railroad invested in building and operating lake steamboats which connected with its trains. A profitable business emerged on Lake Champlain and Lake George.

The Lake Champlain Transportation Company, one of the D&H Railroad's new subsidiaries had a long history of commercially successful steamboat operations. Two vessels from 1907 shown above. In 1874, the D&H Railroad built a new connecting track between its northern Lake George port and the southern port on Lake Champlain to speed transfers of passengers. The two lakes although near to each other have an elevation difference of 225 feet. The Lake George Steamboat Company, the other D&H Railroad's new subsidiaries, began operating a large, fast, side-wheeled steamer 195 feet long with a 30 foot beam powered by a walking beam steam engine giving the vessel a speed of 20 MPH. For the next 75 years some of the finest lake steamers sailed the two lakes and combined with the railroad's passenger trains offered excellent passenger services. Below is a 1907 D&H Railroad timetable showing their coordinated rail and steamboat connections between New York City and Montreal.

Maintaining vessels is a never ending part of the business and the company's marine railway is a key element. In 2000, the Mohican II, originally built in 1908, was again due for a regular inspection, upgrading and general improvements typical of those performed on every vessel worldwide. The vessel was sailed to the company's shipyard at the north end of Lake George and taken out of the water using its unique marine railway.

The final lift of the Mohican II out of the water and up onto the shipyard's work position took almost three hours. As the cradle and ship moved closer to shore, the ship had to be accurately positioned onto the cradle that rose to contact the hull bottom. The operation continued by pulling the cradle once it supported the ship's hull smoothly forward on the railway's tracks until both were completely out of the water and safely positioned high and dry in the shipyard. |

Ships On The Great Lakes Vessels on the Lakes originally powered by sails adapted to steam power after Robert Fulton demonstrated the latest steam vessel technologies in 1807 when his passenger vessel, later named Clermont, sucessfully travelled the 150 miles on the Hudson River between New York City and Albany, NY in 32 hours. Lake Erie's first passenger carrying steamboat was launched in 1819. From various lake ports, a vibrant level of passenger vessel operations grew from the early 1800s during the sailing season. Beginning about 1830, the increasing waves of immigrants from Europe heading for the open lands of the north western states created a opportunity for passenger vessels.

Two other famous passenger liners are the S.S. North Land and the S.S. North West of 4,344 gross tonnage, 7,000 horse power, and a speed of 21 miles an hour. They ply between Buffalo, New York and Duluth, Minnesota and carry their passengers at a speed and amid luxurious accommodations that rival those of the great Atlantic liners," according to the Scientific American. |

The passenger vessels were described by many as floating palaces. They were built specially for the Great Lakes provided city to city service in the 1800s and the early 1900s. Eventually beginning in the 1920s increasingly better highways and cars reduced the number of ship passengers. Many vessels were scrapped. Other ships lived on for years as their owners switched over to the concept of multi-day cruises on the Great Lakes. Unfortunately, that market also declined and by the late 1950s those ships became history. In recent years, passenger vessels on the Great Lakes has experienced a small renaissance including visits by smaller ocean going cruise ships that can pass through the St. Lawrence Seaway locks. |

A Few Great Lakes Steamships |

|

|  | |

Put In Bay | Theodore Roosevelt | City of Cleveland < |

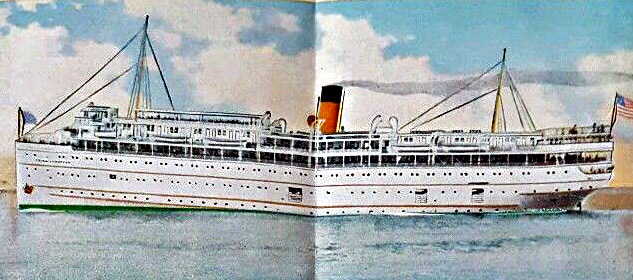

Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay Line's Classic Cruise Ships The Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay Transit Company ordered two large passenger ships designed for cruising on the Great Lakes to be built at the Great Lakes Engineering Works at Ecorse, Michigan. The S.S. North American was launched on January 16, 1913 followed by the S.S. South American on February 21, 1914. The two ships were equipped with three coal-fired Scotch marine boilers that powered the quadruple expansion engine producing 2,200 horsepower and turned the single propeller. They were later converted to oil-fired in the 1920s and a second funnel was added possibly to enhance and streamline the ships' appearance or for techical reasons including adding space to house additional ventilation equipment. That work are other periodic upgrades were done during winter lay ups and maintenance periods. After the 1924 upgrades to oil-fired from coal-fired, the company was able to advertise its two ships were burning oil - No smoke - No soot - No dirt. S.S. North American The S.S. North American was 259 feet long, had a beam of 47 feet, a draft of 17 feet 6 inches and was listed as 2,317 gross tons

Interest in the S.S. North American continued and in 2006, a search effort by Quest Marine successfully located the wreck. According to Quest Marine: "The Great Lakes passenger ship S.S. North American which sank in September of 1967 while on a voyage from Erie PA. to Newport News VA has been found. A research team, this past July aboard Quest Marine's R/V Quest located the ship close to the edge of the continental shelf approximately 140 miles off the New England coast in 250 feet of water…The ship was being towed by the tug Michael McAllister to a shipyard for conversion to a training ship when it sank suddenly on the night of September 13th, 1967. Swells from approaching Hurricane Doria proved too much for the aging ship and contributed to her loss. No one was injured in the sinking and the tug reached port safely. Quest Marine's research team led by Captain Eric Takakjian conducted three days of survey diving operations at the wreck site over the period 15-17 July 2006. Three dive teams of two divers each accomplished photographic and physical measurement documentation of the wreck. The divers included Takakjian, Patrick Rooney, Steven Gatto, Tom Packer, Heather Knowles and David Caldwell. Due to the depth all dive teams breathed custom blended helium based gas mixtures. Decompression was accomplished with the use of multiple oxygen-enriched gases." S.S. South American During the winter lay-up in 1924, the ship suffered a fire requiring some reconstruction of her superstructure. The remainder of her career was successful with her last voyages carrying passengers to the World's Fair in Montreal, Canada in 1967 and she was then retired from Great Lakes service. The S.S. South American was acquired by the Seafarers International Union based in Maryland to replace the S.S. North American that sank before it could converted for use as a training ship. However, after being moved from the Great Lakes to the mid-Atlantic coast, the S.S. South American failed a U.S. Coast Guard inspection and was docked in Camden, New Jersey in 1968. Time and the elements gradually took their toll and the ship was scrapped in 1992 ending her 78 year long career afloat. |

Some Great Lakes Realities The five Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway are shared by seven states in the United States and two provinces in Canada. Maritime operation on the Lakes is generally from April to November due to the lakes freezing over during the winter and most of the Lakers are laid up during those months. An exception for many years were the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company's ferries described earlier in this website's The Railroad Ferries Section. In more recent years, the closed season has been reduced and one factor being U.S. Coast Guard ice breakers on the lakes. Weather is a significant factor during the sailing season due to severe storms that can occur unexpectedly on the waters. The Lakes are very deep and the water described as "incredibly cold at the bottom." Another factor that Great Lakes vessel crews know is the possible affects of the cold and heavy seas on a vessel's structure. "In November 1966…the freighter Daniel J. Morrell upbound in Lake Huron, was caught in an autumn storm, snapped in two and sank before even a radiotelephone message could be sent. Of the thirty-three people on board her, only one was saved. The Morrell was a sturdy 600-footer, a typical laker, which had been built in 1906. Perhaps her steel had become old and fatigued…," according to James P. Barry in his book, The Fate Of The Lakes. He further explained, "The builders of lake vessels have realized the flexibility of their ships and the need to use steel that has sufficient spring…Today the builders carefully determine the flexibility of the steel they use. But if the metal should become less flexible with age, or if the ship should meet a storm that twists her beyond the limits of flexibility, disaster may result." The effects of those realities may have played a role again in November 1975 when the 13,632 ton, 729 ft. laker Edmund Fitzgerald with a crew of 29 was lost in a late autumn storm on Lake Superior. The above YouTube video tells the story. You can skip any commercials after a few seconds. |

Information Works Inc. Transportation - Ships - Trains - Infrastructure Steamboats on America's Rivers and Lakes High Speed Rail - Very Fast and Comfortable The First New York City Railroad Tunnels Under the Hudson River Click to return to -INFORWORKS.COM -homepage Article Copyright 2020. All rights reserved by Richard O. Aichele and InforWorks.com , Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 USA

. . . . . . . |

The Delta Queen was one of America's remaining classic riverboats throughout the early 1980s. Her construction was done over a three year period between 1924 and 1927. Major portions were fabricated overseas such as the propulsion machinery from William Denny & Brothers Ltd., Dumbarton, Scotland and the paddlewheel shaft and the cranks that were forged at the Krupp Stahlwerke AG, Germany. Final construction was completed at the Banner Island Shipyard in Stockton, California.

The Delta Queen was one of America's remaining classic riverboats throughout the early 1980s. Her construction was done over a three year period between 1924 and 1927. Major portions were fabricated overseas such as the propulsion machinery from William Denny & Brothers Ltd., Dumbarton, Scotland and the paddlewheel shaft and the cranks that were forged at the Krupp Stahlwerke AG, Germany. Final construction was completed at the Banner Island Shipyard in Stockton, California.  Reminiscent of the great Misissippi River steamboats of the 1800s, the Delta Queen's gleaming brass, Tiffany style stained glass windows, ornate woodwork, its melodious steam caliope and, down below, surrounded by the aroma of steam and hot oil, the wonderful smoothly working machinery steadily turning the great stern paddle wheel were just some of the features of this grand boat.

Reminiscent of the great Misissippi River steamboats of the 1800s, the Delta Queen's gleaming brass, Tiffany style stained glass windows, ornate woodwork, its melodious steam caliope and, down below, surrounded by the aroma of steam and hot oil, the wonderful smoothly working machinery steadily turning the great stern paddle wheel were just some of the features of this grand boat.  New York Central Number 31 was part of a fleet of tugboats operated by the New York Central Railroad to move barges carrying freight cars to different points in New York Harbor. New York Central Railroad's Tug 31 built as a steam powered tug was still in active service when photographed on the lower Manhattan waterfront in the late 1960s. The active tugs in the mid-1900s included many steam powered tugs and ferries although use of diesel engine power resulted in the rertirement of older steam power vessels.

New York Central Number 31 was part of a fleet of tugboats operated by the New York Central Railroad to move barges carrying freight cars to different points in New York Harbor. New York Central Railroad's Tug 31 built as a steam powered tug was still in active service when photographed on the lower Manhattan waterfront in the late 1960s. The active tugs in the mid-1900s included many steam powered tugs and ferries although use of diesel engine power resulted in the rertirement of older steam power vessels.  The Port of New York's towing companies have included Moran Towing and Transportation. McAllister Towing and Dalzell Towing with its Dalzellido of New York shown crossing Lower New York Harbor toward New Jersey with the Statue of Liberty in the background about fifty years ago. Tugboats had the important role of not only asssisting in docking ocean going ships but for the railroads by providing the power to move barges filled with railroad freight cars and often passenger cars with passengers on-board.

The Port of New York's towing companies have included Moran Towing and Transportation. McAllister Towing and Dalzell Towing with its Dalzellido of New York shown crossing Lower New York Harbor toward New Jersey with the Statue of Liberty in the background about fifty years ago. Tugboats had the important role of not only asssisting in docking ocean going ships but for the railroads by providing the power to move barges filled with railroad freight cars and often passenger cars with passengers on-board.

As the map shows, the C&O's railroad ferry service had been an integral element of the C&O Railway's operating system in Michigan. Since then, changes in demographics, people's modes of travel, railroad consolidations and other economic realities led to reduced ferry travel on those routes and retirement of the ferry vessels by the railroad.

As the map shows, the C&O's railroad ferry service had been an integral element of the C&O Railway's operating system in Michigan. Since then, changes in demographics, people's modes of travel, railroad consolidations and other economic realities led to reduced ferry travel on those routes and retirement of the ferry vessels by the railroad.

In earlier days along the river, the mighty Mississippi River, the Packet Boat

Belle of the Bends stops at the landing in Vicksburg, MS transfering passengers and cargo coming from or destined for other Mississippi River ports.

In earlier days along the river, the mighty Mississippi River, the Packet Boat

Belle of the Bends stops at the landing in Vicksburg, MS transfering passengers and cargo coming from or destined for other Mississippi River ports. The steamer St. Johns, along with her running mate the Drew provided

the People's Evening Line's red plush and tassel overnight service on the Hudson River between New

York City and Albany, NY. The St. John was 385 feet long and powered by a massive walking

beam steam engine with a 76 inch cylinder and 15 foot stroke. The boat burned in January, 1885.

The steamer St. Johns, along with her running mate the Drew provided

the People's Evening Line's red plush and tassel overnight service on the Hudson River between New

York City and Albany, NY. The St. John was 385 feet long and powered by a massive walking

beam steam engine with a 76 inch cylinder and 15 foot stroke. The boat burned in January, 1885. During the first half on the 20th Century, the overnight boats on the Hudson gradually

gave way to daytime runs to the steamers, such as the Robert Fulton, became thriving, lively daytime excursion businesses.

During the first half on the 20th Century, the overnight boats on the Hudson gradually

gave way to daytime runs to the steamers, such as the Robert Fulton, became thriving, lively daytime excursion businesses. The typically large numbers of passengers and spectators on the pier in Kingston, New York shown greeting the Hudson River Day Line's 5,500 passenger steamer Hendrick Hudson making a regular stop on its upriver journey. Built in 1906 by the T. S. Marvel Shipbuilding Company in Newburgh, New York with an all steel hull and superstructure, the vessel was 400 feet long overall, had a beam of 45.1 feet at the gunwales and 82 feet over the guards and a draft of only 7.5 feet allowed to it to safely navigate the shallower upper portion of the Hudson River. The Hendrick Hudson was equipped with side paddle wheels powered by a 3 cylinder compound direct-actiing steam engine that produced 6,200 horsepower built by W. & A. Fletcher Co. Designed for service between New York City and Albany, New York, the Hendrick Hudson made her maiden voyage at speeds up to 24 milies per hours. This Hudson River boat entered service in August 1906 and was singularly impressive. Passengers could climb to the top deck, known as the hurricane deck, for views of the passing river scenes. This deck also included two parlor rooms and officers' staterooms. Below was deck number 3, the promenade deck, that included large enclosed observation rooms one forward and the other toward the stern. The second deck's main saloon was outfitted with the eras fine decorative appointments. The dining room was located below on the main deck offering guests the maximum cruising stability and smoothness through the river waters.

The typically large numbers of passengers and spectators on the pier in Kingston, New York shown greeting the Hudson River Day Line's 5,500 passenger steamer Hendrick Hudson making a regular stop on its upriver journey. Built in 1906 by the T. S. Marvel Shipbuilding Company in Newburgh, New York with an all steel hull and superstructure, the vessel was 400 feet long overall, had a beam of 45.1 feet at the gunwales and 82 feet over the guards and a draft of only 7.5 feet allowed to it to safely navigate the shallower upper portion of the Hudson River. The Hendrick Hudson was equipped with side paddle wheels powered by a 3 cylinder compound direct-actiing steam engine that produced 6,200 horsepower built by W. & A. Fletcher Co. Designed for service between New York City and Albany, New York, the Hendrick Hudson made her maiden voyage at speeds up to 24 milies per hours. This Hudson River boat entered service in August 1906 and was singularly impressive. Passengers could climb to the top deck, known as the hurricane deck, for views of the passing river scenes. This deck also included two parlor rooms and officers' staterooms. Below was deck number 3, the promenade deck, that included large enclosed observation rooms one forward and the other toward the stern. The second deck's main saloon was outfitted with the eras fine decorative appointments. The dining room was located below on the main deck offering guests the maximum cruising stability and smoothness through the river waters. The excursion steamer Hendrick Hudson departing from the Hudson Day Line's river landing at Poughkeepsie, NY heading downriver to New York City in the early 1900s.

The excursion steamer Hendrick Hudson departing from the Hudson Day Line's river landing at Poughkeepsie, NY heading downriver to New York City in the early 1900s. Many large American inland lakes have a long history of water transportation that served shoreline towns and individual properties. In 2019, the steamboat Minne - Ha - Ha is still cruising the waters of Lake George, New York.

Many large American inland lakes have a long history of water transportation that served shoreline towns and individual properties. In 2019, the steamboat Minne - Ha - Ha is still cruising the waters of Lake George, New York.

With various vessels, the Lake George Steamboat Company subsidiary continued until 1945. It then had one aging steel hulled steam powered vessel called the Mohican II, a small dock and a small shipyard with a marine railway. New owners, that still own the company today, acquired it in 1945 and began a steady effort to rebuild the company and its facilities. Now, with three first class excursion vessels, passenger service in season is again popular on Lake George. The stern wheeler steamboat Minne-Ha-Ha was the first vessel built by the new management at its shipyard on the lake in 1969. She was later extensively enlarged and improved in 1998. The company's next major ship construction program at its lake front shipyard created the 189.5 foot long diesel powered Lac du Sacrement. It is a remarkably accurate recreation of the old Hudson River passenger steamer Peter Stuyvesant but reduced to a 3/4 scale.

With various vessels, the Lake George Steamboat Company subsidiary continued until 1945. It then had one aging steel hulled steam powered vessel called the Mohican II, a small dock and a small shipyard with a marine railway. New owners, that still own the company today, acquired it in 1945 and began a steady effort to rebuild the company and its facilities. Now, with three first class excursion vessels, passenger service in season is again popular on Lake George. The stern wheeler steamboat Minne-Ha-Ha was the first vessel built by the new management at its shipyard on the lake in 1969. She was later extensively enlarged and improved in 1998. The company's next major ship construction program at its lake front shipyard created the 189.5 foot long diesel powered Lac du Sacrement. It is a remarkably accurate recreation of the old Hudson River passenger steamer Peter Stuyvesant but reduced to a 3/4 scale. Positioning the Mohican II over a submerged cradle riding on submerged railroad tracks was performed flawlessly by the vessel's captain and the divers in the water.

Positioning the Mohican II over a submerged cradle riding on submerged railroad tracks was performed flawlessly by the vessel's captain and the divers in the water.

Maritime traffic from the early 1800s was primarily cargo ships with a large part of the traffic related to the steel industry located near the lakes. Transportation of wheat and other bulk commodities from midwestern lake ports often went to the eastern end inland lake ports such as Buffalo, New York where the cargo was transferred to railroads. In 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway was completed allowing ocean going vessels to sail into all of the Lakes.

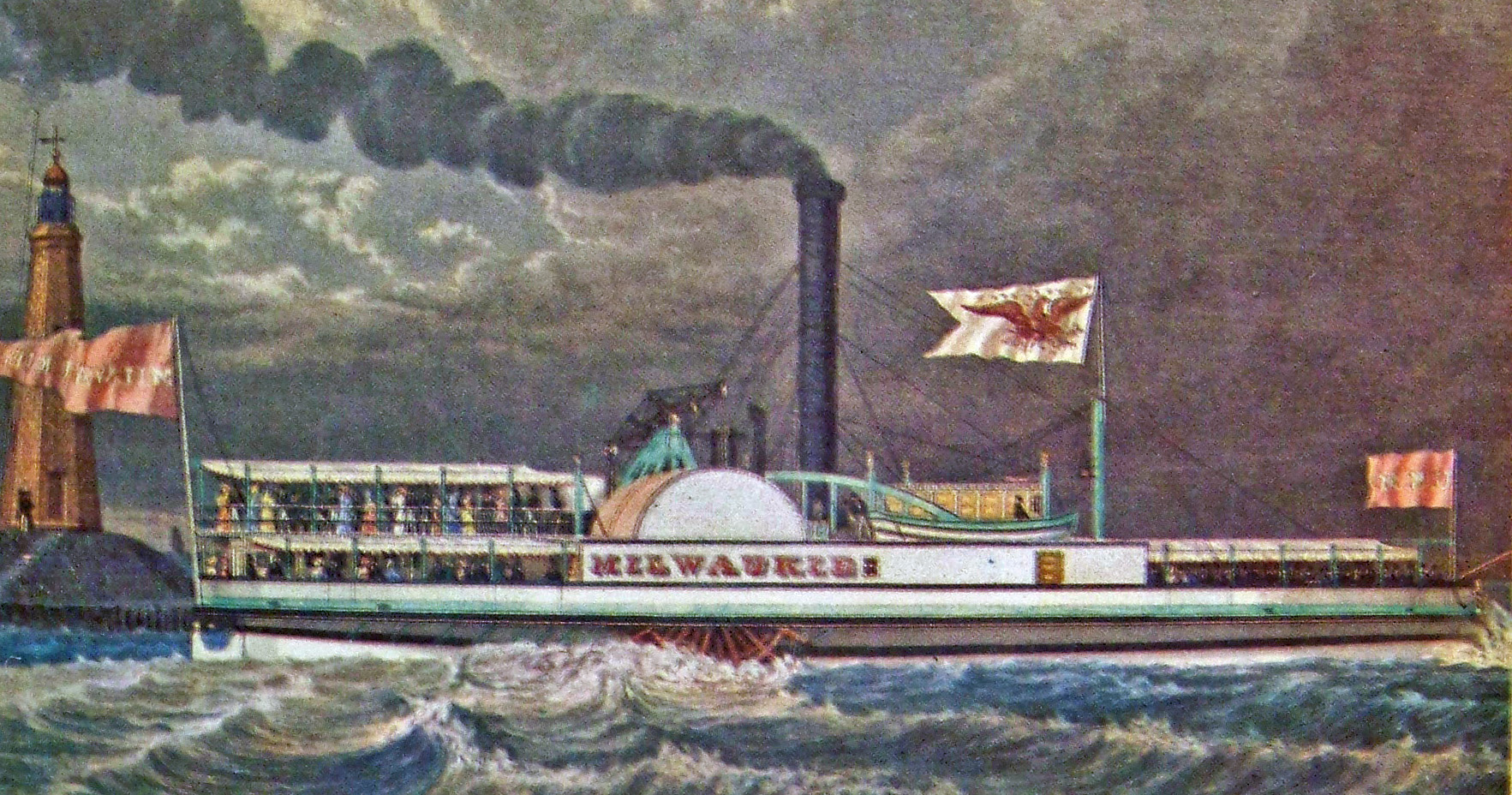

Maritime traffic from the early 1800s was primarily cargo ships with a large part of the traffic related to the steel industry located near the lakes. Transportation of wheat and other bulk commodities from midwestern lake ports often went to the eastern end inland lake ports such as Buffalo, New York where the cargo was transferred to railroads. In 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway was completed allowing ocean going vessels to sail into all of the Lakes. The 401 ton, 172 ft. long S.S. Milwaukie was built in 1837 at Grand Island, NY. The ship's operating career was short when she was wrecked in 1842 while sailing on Lake Michigan.

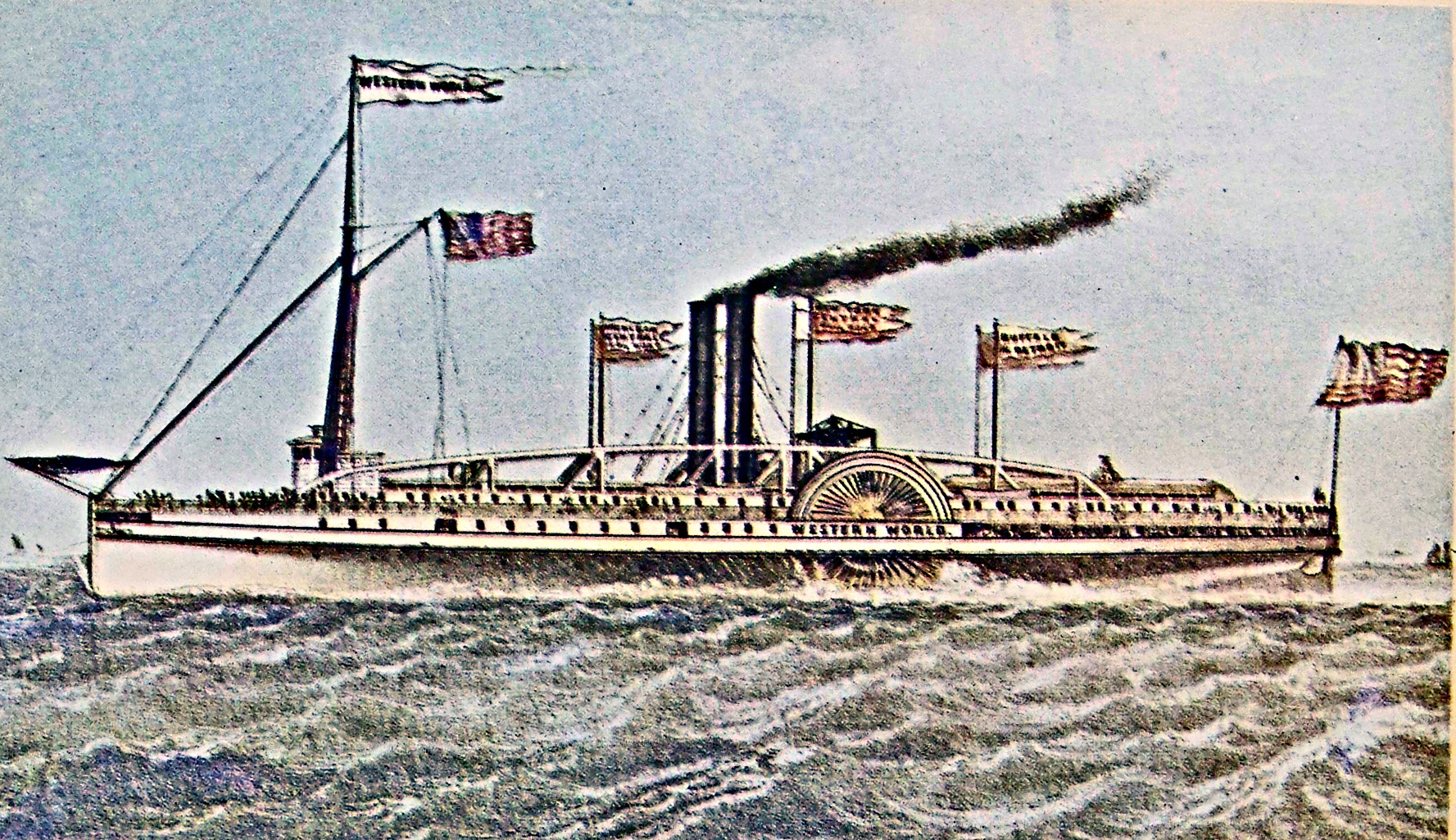

The 401 ton, 172 ft. long S.S. Milwaukie was built in 1837 at Grand Island, NY. The ship's operating career was short when she was wrecked in 1842 while sailing on Lake Michigan. The railroads also benefitted from lake passenger vessels at times. When the New York Central Railroad from New York City still only went west to the eatern end of Lake Erie in Buffalo, NY and its associated Michigan Central Railroad going east ended at the western end of Lake Erie, the transportation void at Lake Erie was filled by lake steamers. One of the passenger steamers was the S.S. Western World built in 1854. The 337 ft. long, 2,002 ton was described as "the finest steamer the Lakes would have for decades to come" but the initial intended service lasted only three years. Once the New York Central finished its new tracks along the lake's shoreline and connected with the Michigan Central, the S.S. Western World and her sister ships were laid up and later scrapped. The railroads also operated their own Great Lakes steamship companies to serve hotels and summer resorts in remote areas far from their neareast lakefront rail terminals.

The railroads also benefitted from lake passenger vessels at times. When the New York Central Railroad from New York City still only went west to the eatern end of Lake Erie in Buffalo, NY and its associated Michigan Central Railroad going east ended at the western end of Lake Erie, the transportation void at Lake Erie was filled by lake steamers. One of the passenger steamers was the S.S. Western World built in 1854. The 337 ft. long, 2,002 ton was described as "the finest steamer the Lakes would have for decades to come" but the initial intended service lasted only three years. Once the New York Central finished its new tracks along the lake's shoreline and connected with the Michigan Central, the S.S. Western World and her sister ships were laid up and later scrapped. The railroads also operated their own Great Lakes steamship companies to serve hotels and summer resorts in remote areas far from their neareast lakefront rail terminals.  The fast growing shipbuilding industry on the Great Lakes often creatively evolved ship designs for the unique challenges of the lakes. "The whaleback is a distinctive type which has been evolved by the lake ship builders and a large fleet of them has already been turned out of the Duluth yards. The S.S. Christopher Columbus a passenger whaleback was familiar to visitors to the World's Fair. The ship is a beautifully modeled vessel, 362 feet in length, with a beam of 42 feet and a high speed.

The fast growing shipbuilding industry on the Great Lakes often creatively evolved ship designs for the unique challenges of the lakes. "The whaleback is a distinctive type which has been evolved by the lake ship builders and a large fleet of them has already been turned out of the Duluth yards. The S.S. Christopher Columbus a passenger whaleback was familiar to visitors to the World's Fair. The ship is a beautifully modeled vessel, 362 feet in length, with a beam of 42 feet and a high speed.

By the 1960s, the Great Lakes cruise travel market had declined substantially. Both the S.S. South American and the S.S. North American advertising had promoted the ships and their operation as: The only exclusively passenger ship on the Great Lakes. As time went on, the lack of any supplemental income such as package express may have affected the operation's overall profitability.

By the 1960s, the Great Lakes cruise travel market had declined substantially. Both the S.S. South American and the S.S. North American advertising had promoted the ships and their operation as: The only exclusively passenger ship on the Great Lakes. As time went on, the lack of any supplemental income such as package express may have affected the operation's overall profitability.  The ship sailed for the original owners until 1963 when she was sold to a to a company that operated her for one year for cross lake sailing between Erie, Pennsylvania, USA and Port Dover, Ontario, Canada. The ship was retired in 1964. Several attempts to secure a new a operator failed. At auction, she was acquired by the Seafarers International Union for use as a training ship. While under tow from the Great Lakes to Maryland the ship suddenly sank in the Atlantic Ocean in the area of Nantucket ending her 54 year long career.

The ship sailed for the original owners until 1963 when she was sold to a to a company that operated her for one year for cross lake sailing between Erie, Pennsylvania, USA and Port Dover, Ontario, Canada. The ship was retired in 1964. Several attempts to secure a new a operator failed. At auction, she was acquired by the Seafarers International Union for use as a training ship. While under tow from the Great Lakes to Maryland the ship suddenly sank in the Atlantic Ocean in the area of Nantucket ending her 54 year long career. The S.S. South American was slightly larger than her sister ship at 290 feet long, had a beam of 47 feet and was listed as 2,662 gross tons. Otherwise she had the same technical and construction features as her sister ship the S.S. North American..

The S.S. South American was slightly larger than her sister ship at 290 feet long, had a beam of 47 feet and was listed as 2,662 gross tons. Otherwise she had the same technical and construction features as her sister ship the S.S. North American..