Copyright 2020 by Richard O. Aichele - email rottoa@gmail.com - and InforWorks.com |

"For the last half hour our men watched and held themselves ready... Then for one wild confused moment they knew that they were running towards that unknown land which they could see in the dust ahead. For a moment, they saw the parapet with the wire in front of it... Then, too often, for too many of them, the ground they were crossing flew up in shards and sods and gleams of fire from the enemy shells, and those runners never reached the wire, but saw, perhaps a flash and the earth rushing nearer and then saw nothing more at all, forever and forever and forever."

That small event at the Somme in July 1916 described by John Masefield, an English writer, had been preceded by days of English heavy artillery bombardment of the German trenches on the other side of No Man's Land as the English infantry waited for order to attack. The soldiers on both sides were fighting on and for a wartorn usually barren landscape as they lived in trenches and underground bunkers only hundreds of yards apart from each other. Between the trench lines was No Man's Land where many attackers died while trying to reach the other side. It was a scene repeated millions of times during the years 1914 to 1918. They were German, French, English, Austrian, Belgian, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Italian and later American soldiers on both sides who fell as bullets and explosions ravaged the ground and everything on it. Recovery of wounded soldiers who initially survived in No Man's Land was rarely possible. Recovery of bodies was unlikely. Masefield described a typical scene in the Somme: "The bodies of two English soldiers were buried and then unburied by the rain as they lay in No Man's Land outside the English wire in what was one of the lonliest places in the field...They are among many English graves marked hurriedly by the man's rifle thrust into the ground."

|

|

Empathy In 1924, eight years after the Battle of Verdun the American journalist and war correspondent Webb Miller went to the Verdun battlefields and wrote this article: "I visited a grizzled French priest who lived on the summit near Fort Vaux. He had dedicated his life to gathering bones which he placed in a temporary mortuary. There I saw piles of skulls with great jagged shrapnel holes, shattered arm and leg bones, and bits of skeletons, all of which he had collected. They were to be placed in fifteen huge caskets, one for each of the fifteen sectors of the battlefield. Each casket in turn would represent thousands of unknown soldiers. The caskets were to be placed in a huge memorial which the French were constructing on the hills.". It staggered the imagination to think that more than 300,000 French bodies were never identified and thousands upon thousands never found; that the greater part of the 600,000 German dead also remained unidentified While leaving Verdun in the grimy train I caught a brief glimpse of what this place meant to sorrowing millions. In one corner of the shabby train compartment huddled a thin, careworn old German woman, poorly dressed in obviously homemade clothing. As the train drew up the slopes she nervously brushed the moisture from the rain swept window for a last look at the desolate hills where more than 600,000 of her countrymen had been slaughtered. Then she subsided into the corner, weeping quietly; furtively wiping her eyes with a sodden handkerchief. I asked if she had lost relatives in the battle of Verdun. She broke into tears. 'Yes, my two sons and my husband. Nobody knows where they fell. I could only walk over the terrible fields. I have been saving eight years to make this trip. I can never do it again. Everything is gone. Oh, this horrible war!" The train arrived at a station and the German woman got off and a French peasant woman came into the compartment. Miller got into conversation with her and told her about the German woman. The French woman kept silent for a few minutes, then tears filled her eyes. "Our countries were enemies but I can't help pitying that poor German woman. It must be terrible to come all this way and not know where her dead lie. I come every year at this time. My husband, my son, and my brother are up on those hills. We know where their bodies lie and that is some consolation." - - - - - - - - - - - - |

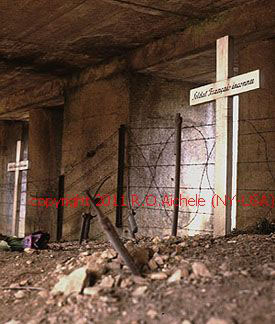

The poignant Trench of Bayonets Memorial to the 170 unknown French soldiers of the 1st Battalion of the 137th who endured a heavy bombardment on June 11, 1916. While waiting for an enemy assault, their rifles with fixed bayonets were propped up against the parapet within reach for they had in their hands bombs to be used as the first means of repelling the probable attack. Then heavy shells falling in front, behind and on the trench collapsed it instantaneously leaving only the soldiers' rifle barrels and bayonets protruding.

|

The Search For The Missing Never Ends It is one hundred years since the battles of the Great War on the land that was the Western Front stretching from the English Channel southward across Belgium, Luxemburg and France to the border of Switzerland. Artifacts of that war including parts of guns, helmets, grenades and shells are frequently found and removed. Among the still thousands of buried shells are gas shellls which as they rust through leak their poison contents into the ground killing all vegetation within a 20 or 30 foot radius. For many on both sides of the Western Front, the only shelter from exploding shells were the dugouts built as part of the trench systems. An unknown number remain buried and forgotten in the earth. Recoveries have been made since 1918. This discovery of missing soldiers was reported in the British newspaper Daily Mail: "French archaeologists stumbled upon the mass grave on the former Western Front in eastern France during excavation work for a road building project. The bodies of 21 German soldiers entombed in a perfectly preserved World War One shelter have been discovered 94 years after they were killed. The men were part of a larger group of 34 who were buried alive when a huge Allied shell exploded above the tunnel in 1918 causing it to cave in. Thirteen bodies were recovered from the underground shelter, but the remaining men had to be left under a mountain of mud as it was too dangerous to retrieve them." |

|

|

|

Dugout Stairway |

Rusted German Helmet |

A Soldier's Rifle |

Photo Credits: PAIR Archeologle BNPS Co. UK and The Daily Mail Co.UK VIEW this link for the complete article The Daily Mail This recent discovery and archeological excavation is a reminder that along the entire areas of the Western Front thousands of soldiers from both sides died where they fell in the trenches, shell holes, no-mans-land and in the barbed wire. Their remains were commonly churned up by the incessant shell explosions making them part of the earth they had fought on. Since 1918, as remains are located they are properly buried such as these soldiers at Carspach, France. Most men were listed as Missing In Action and will forever remain out there in the battlefields where they fell. |

For my enemy is dead - a man devine as myself is dead." "That the hands of the sisters Death and Night, incessantly, softly, wash again and ever again this soil'd world." Walt Whitman, American writer

"And for what?" A frequent question by Eugen R. Aichele, German Army kanonier 1916-1918, as he visited soldiers' cemetaries and walked the battlefields where 50 years earlier he had served and was wounded. |

InforWorks . com Great War Histories A Veteran Revisits the Western Front 50 Years Later |

"Jutland - Clash of the Battle Cruisers Return to INFORWORKS.COM homepage

Copyright 2022 by Richard O. Aichele & InforWorks.com

PO Box 4725, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866 USA

Your comments or questions are welcome. Send emails to rottoa@gmail.com Thank you for visiting this website. . . . . . . . |

The heavy fighting endured by German and French soldiers around Verdun was typical of events that created large numbers of the missing in action on both sides. Casualties from heavy shelling for days on end led to appalling casualties. "One French officer describes how he was buried three times that day in his trench, and dug out each time by his men. Others were less fortunate. Of one battalion, only three men were said to have survived; many of the remainder were simply buried alive by the shells," wrote Alistair Horne in The Paths of Glory describing the realities on Cote 304 at Verdun. During the four years of war, hundreds of thousands of soldiers were never recovered simply because their shattered remains had become a part of the battlefields' constantly churned up earth.

The heavy fighting endured by German and French soldiers around Verdun was typical of events that created large numbers of the missing in action on both sides. Casualties from heavy shelling for days on end led to appalling casualties. "One French officer describes how he was buried three times that day in his trench, and dug out each time by his men. Others were less fortunate. Of one battalion, only three men were said to have survived; many of the remainder were simply buried alive by the shells," wrote Alistair Horne in The Paths of Glory describing the realities on Cote 304 at Verdun. During the four years of war, hundreds of thousands of soldiers were never recovered simply because their shattered remains had become a part of the battlefields' constantly churned up earth. If possible, the dead were buried by their comrades in field graves or field cemetaries. Behind the Front Line, the burials in times of warfare quiet times far enough behind the front trench line shellings. This Wurttembergishe 49th Feld Artillery Regiment burial photo of a deceased German Army soldier surrounded by his fellow soldiers is one example. Within hours, enemy artillery shells could have been turning up that earth again.

If possible, the dead were buried by their comrades in field graves or field cemetaries. Behind the Front Line, the burials in times of warfare quiet times far enough behind the front trench line shellings. This Wurttembergishe 49th Feld Artillery Regiment burial photo of a deceased German Army soldier surrounded by his fellow soldiers is one example. Within hours, enemy artillery shells could have been turning up that earth again. (Right) A warfront cemetary for soldiers of the Wurttembergishe 185th Feld Artillery Regiment after fighting in the Champagne Region. Drawn by the German Army artist Erwin Aichele in 1916.

(Right) A warfront cemetary for soldiers of the Wurttembergishe 185th Feld Artillery Regiment after fighting in the Champagne Region. Drawn by the German Army artist Erwin Aichele in 1916.

One major recent discovery and recovery has been made in the Alsace town of Carspach next to Altkirch located at what became in 1914 the southern end of the Western Front at the Swiss border. Immediately after war was declared in 1914, the French Army from Belfort crossed the frontier and captured Altkirch and Carspach then advanced further capturing Mulhausen. All areas were later recaptured by German forces. The fighting there effectively became a trench warfare stalemate fought mainly by artillery fire until 1918.

One major recent discovery and recovery has been made in the Alsace town of Carspach next to Altkirch located at what became in 1914 the southern end of the Western Front at the Swiss border. Immediately after war was declared in 1914, the French Army from Belfort crossed the frontier and captured Altkirch and Carspach then advanced further capturing Mulhausen. All areas were later recaptured by German forces. The fighting there effectively became a trench warfare stalemate fought mainly by artillery fire until 1918.